10th April 2024 In Emerson Stories, Feature By Adeline Garman

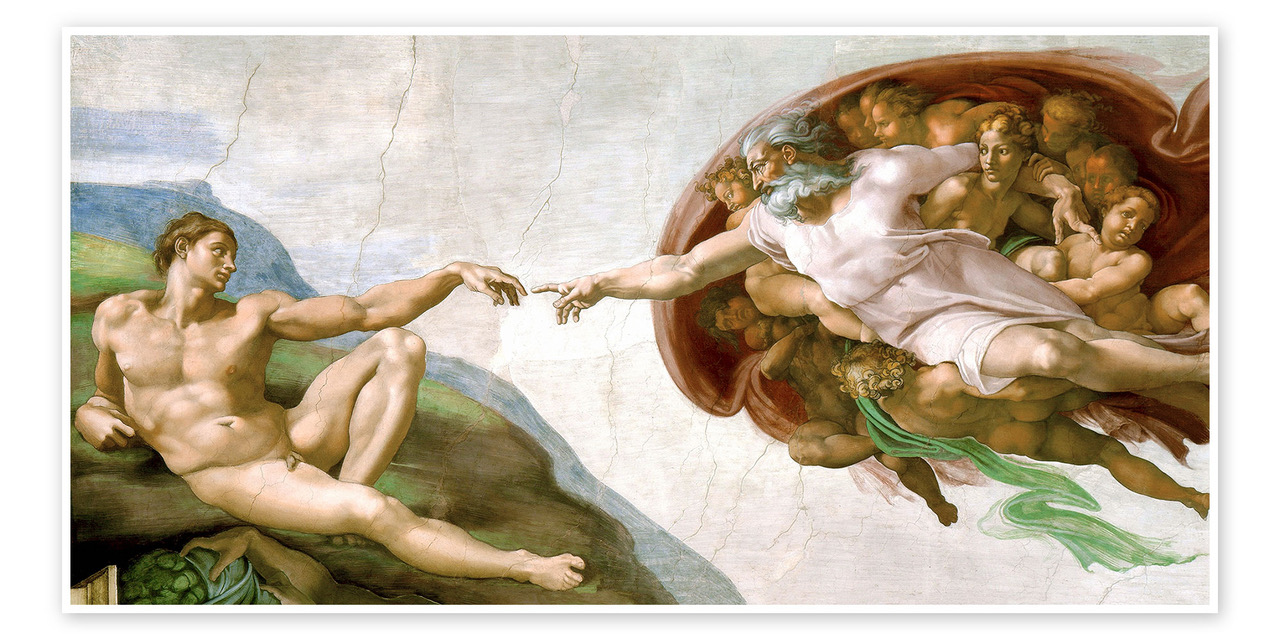

The Turbulent Life of Michelangelo

Michelangelo is one of the Renaissance artists whose turbulent life has excited particular interest. His contentious relations with the Pope are legend, and have been engraved into the public imagination by Irving Stone’s The Agony and the Ecstasy, also made into a film with Rex Harrison and Charlton Heston almost sixty years ago. Ross King’s book Michelangelo and the Pope’s Ceiling came out some twenty years ago revisiting the battle of wills between Buonarroti and Julius II. The riddle of Michelangelo’s unfinished works, the outrage in his day at the nudity in the Sistine Chapel altar wall fresco, the ecclesiastical disapproval of his departure from conventional iconography, and the bitter competition with some of his contemporaries, have all contributed to the sensational fascination with this great master.

There continues to be a stream of new, insightful biographies; art historians today contest some of the attributions; the academic literature is alive with conflicting interpretations. Michelangelo died in 1564, the year Shakespeare was born, and both these masters share an interesting characteristic; in addition to their principal work they both wrote sonnets. For both these artists their private poetry was a refuge of personal soul dynamics that provided a means to balance the mighty universal inspirations they served in their main works. It might be tempting to think Shakespeare wrote Hamlet because he had a problem with his father and that Michelangelo’s occupation with the naked human body derived from his personal proclivities. Such interpretations miss the point.

Let us not look to find evidence of autobiography in the work of artists of this calibre. Shakespeare brings his own skill of language and stagecraft, and Michelangelo brings his physical strength and stamina with fine coordination of hand and eye. These personal capacities selflessly serve the mighty, intuitively grasped tasks that come from imaginations of our shared human evolution. The biography of such artists’ inspiration may not be unconnected with their personal biography, but what makes their work great art is precisely what rises above the personal and appeals to and can be recognised as part of our universal spiritual heritage and striving.

The metamorphosis in Michelangelo’s work as architect, sculptor, and painter, and the vision it serves have been part of my research for a number of years. Buonarroti comes back to the human form again and again in a quest, at first, to regain what we lost in paradise. The turning point in his life’s work (at his third moon node!) is a reorientation that leads to a new conception of our social potential in the future.

In the seminar at Emerson College 27th – 31st May, we will explore this development through lectures, observation, sketching, and active installations, and in connection with what Rudolf Steiner called the Phantom in the lecture cycle From Jesus to Christ (GA 131). Michelangelo was indeed an emissary from the Supersensible School of Michael who brought through his art some of what four hundred years later Rudolf Steiner brought in the Christology of Spiritual Science.

More information about the week long seminar can be found here.

This article was originally published in ASinGB Magazine in Spring 2024 and is reproduced here with kind permission.